II. Macroeconomic Sustainability

II.A – Macroeconomic Balance: The First among Economic Fundamentals

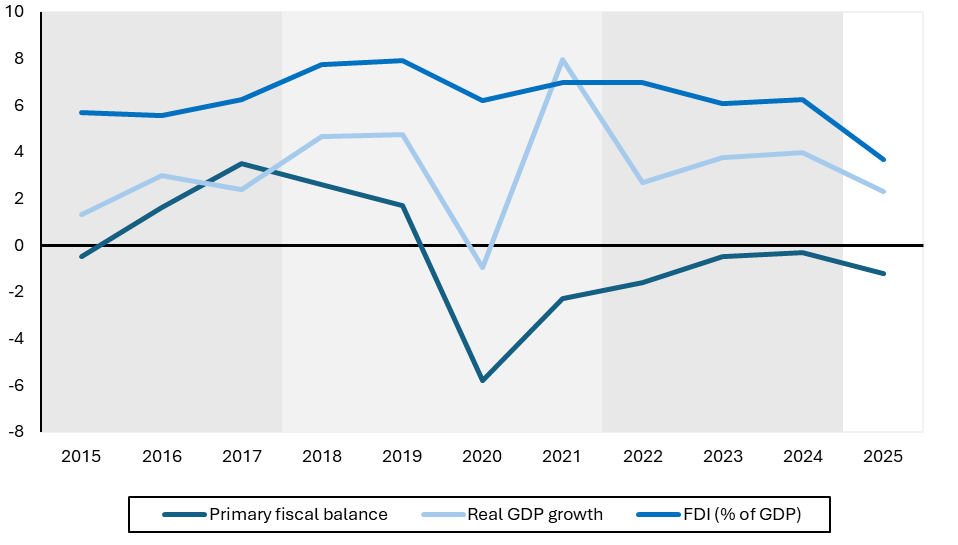

1. Macro-developments since the fiscal consolidation

Table 1. Three macroeconomic periods: key determinants

| Indicator | 2015-2017 | 2018-2021 | 2022-2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth | 2.2 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 2.3 |

| Drivers | ||||

| Primary fiscal balance (change during period) | 3.0 | -4.9 | 1.3 | -1.2 |

| Investment contribution to GDP growth | 1.0 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Government CAPEX (% of GDP) | 2.7 | 5.2 | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| FDI (% of GDP) | 5.8 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 3.7 |

| Exports contribution to GDP growth | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Context | ||||

| Inflation, average annual % change | 2.0 | 2.4 | 9.7 | 3.9 |

| Unemployment rate (%), end of period | 14.5 | 11.0 | 8.6 | 8.2 |

| Vacancies-unemployment ratio | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.48 |

Annual averages unless stated otherwise

In addition, Serbia’s performance during the COVID crisis had been particularly impressive as its GDP declined by only 1% in 2020. This largely reflected the strong FDI pipeline in the construction sector, that continued throughout 2020 as well as the composition of the country’s output, with a heavy reliance on the agri-food sector, as well as impressive flexibility and performance of Serbia’s SME exporters.

The 2021-2024 Period: Energy Crisis and Inflation

The following period of 2021-2024 in Serbia, as elsewhere, was marked by the energy crisis set off by the war in Ukraine, and accelerated inflation. Specifically, Serbia, which in the preceding years maintained inflation rates inside the Central Bank’s target corridor, faced an increasing price level much higher than in European counterparts.

The inflation rate peaked at 16% at the beginning of 2023, driven mostly by the surge in food prices, with a lagging manufacturing sector adjusting to supply shocks. While food prices were the primary contributor to headline inflation in Serbia, the energy component exhibited a markedly different adjustment pattern compared to the European Union.

In addition to exogenous geopolitically caused shocks in the energy sector, a substantial part of the crisis can be attributed to endogenous problems in this sector that unraveled in Serbia in 2023 thanks to a major breakdown in EPS late in 2021. The Fiscal Council estimates that losses of Serbian state-owned electricity and gas companies to be around 1 billion EUR, most of which is financed directly from the government budget.

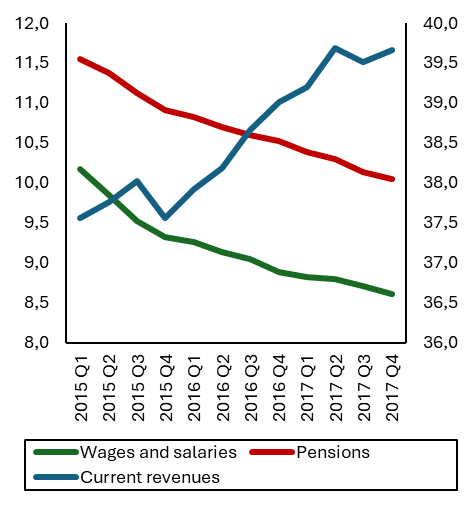

Considering the exorbitant costs of the rehabilitation of EPS’s productive capacity, and that the fiscal framework needed to be kept under control, many expenditures were sacrificed between mid-2022 and mid-2023. Thus, government salaries were kept essentially frozen despite the jump in living costs, sharply eroding their purchasing power and government investment plans were curtailed, with some flagship projects such as the National Stadium, postponed.

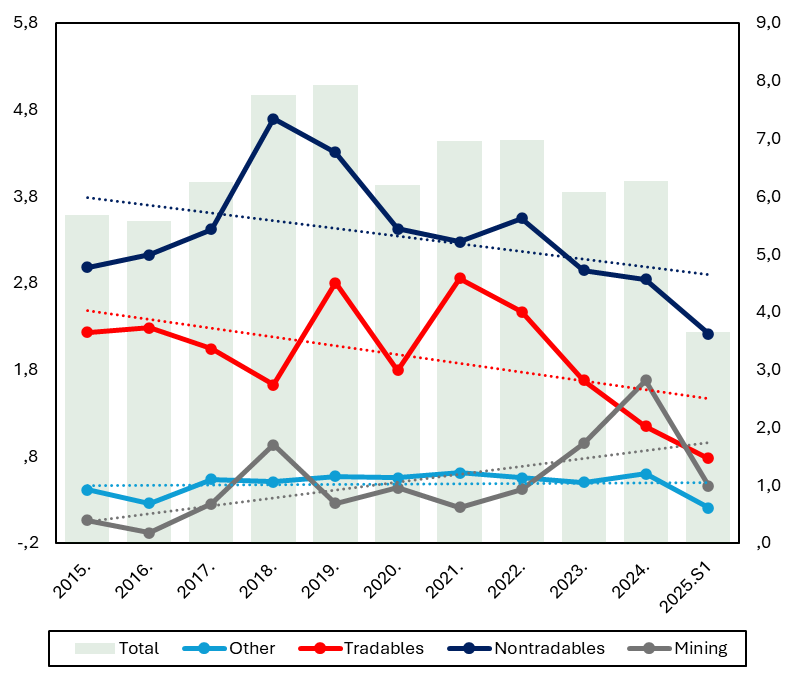

Knowledge Services and ICT Growth

In addition to mining and construction, the main contributor to growth in this period were ICT and professional services. Knowledge service exports grew 31% on average annually over this period, reaching 5% of GDP in 2024. While this is partly the result of the global transformation in the role of the ICT sector globally in the aftermath of the COVID crisis, ICT service imports increased by substantially less – by 23%. This suggests that Serbia is among the countries that showed a strong competitive performance in this regard.

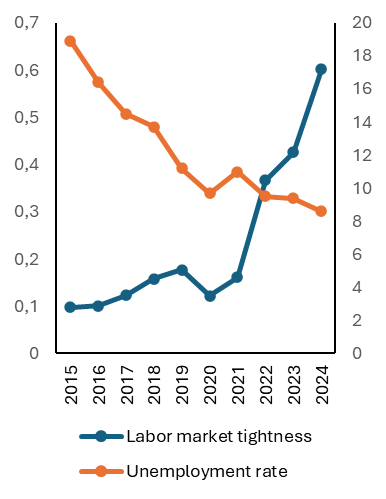

Labor Market Tightening

Among the economic phenomena characterizing Serbia’s macroeconomic developments over 2022–24, possibly the one with the most far-reaching effects is the extreme tightening of the labor market. Employment in Serbia had reached bottom in 2014, with around 1.845 million employees with unemployment peaking in 2012 at 24%. From that point employment increased gradually at first, and with the large employer incentives accelerated further.

In only three years, however, the number of job vacancies increased to 223,000, while the number of unemployed was 370 thousand. This disparity is strongly reflective of a deep structural mismatch and rigidities of the labor market, whose fixing requires a radical reform and strengthening of Serbia’s institutions.

Not surprisingly, this period is also characterized by the beginning of a sharp acceleration of real wages. It did not begin immediately. As said, public wages were kept nearly frozen at first, and possibly because of that, private wages also took some time to start adjusting. However, by the end of 2024, real wages stood 14% higher than at the end of 2021 and have continued to grow since.

Macroeconomic Developments in 2025

The year 2025 marked a departure from the previous nearly decade of relatively strong growth. Starting from the very first quarter of the year, GDP is estimated to have grown about 2% year-on-year in every quarter.

The drop came as a surprise and it is hard to resist the impression of an immediate connection between the onset of popular protests in November 2024 and the sharp drop in inflows of FDI. However, there is little doubt that this slowdown has deeper roots:

- Mining investment completion: The current Chinese investment projects in mining in eastern Serbia were nearing completion

- ICT sector changes: To the extent that the inflows into ICT were connected to Russian and Ukrainian immigrants, they would have been ending; moreover, the disruption of the type of ICT present in Serbia (mostly outsourcing and coding) by AI is beginning to gather steam

- Construction wind-down: If the expansion of construction capabilities was connected to Chinese capital readying for the works on Expo 2027, it would now be winding down

Another predictable slowdown factor has been government infrastructure investment. These expenditures had reached well over 7 percentage points of GDP in 2024, and there is no further where to go. In fact, the fiscal strategy in 2024, and again now in 2025, envisage its slight slowdown over the coming years.

Export Performance in 2025

Growth in 2025 seems to have been supported primarily by household consumption, owing to the large increase in real wages (including in the public sector) and by exports. Exports of goods increased at a pace similar to that in 2024 (8.1% nominal and approximately 5.9% in real terms), but their net effect was dampened by increased imports as the real exchange rate has increased. Services exports slowed to 6.6% year-on-year, reflecting a decline in tourism and a slowdown in the IT sector.

This solid performance of exports has been supported by:

- A ramp-up of electric vehicle production at the Stellantis plant in Kragujevac (+25.8% through October)

- Tire exports (+18.1%)

The largest negative contribution came from agriculture, which saw a decline of -14.8%.

Of significant concern is the apparent very weak performance, possibly decline, of SME exports. The 2024–2025 period has, for the first time, resulted in a significant lag behind the export performance of foreign-owned firms.

Outlook

As the European economy is turning the corner and FDI outflows appear to be bottoming out, there is little doubt that the underlying slowdown in FDI has been affected by negative developments in the broader capital flows environment, and it could soon start recovering. EU, and especially Germany’s, capital outflows had been declining since before the COVID crisis. Serbia had been beating the odds in attracting them, for a while.

Nevertheless, the footloose low-wage manufacturing that provided significant employment in the previous periods have begun to leave Serbia and will not be coming back. Trade unions estimate that some 9,000 of those jobs will be lost in 2025. In many of the Southeastern towns in Serbia they have become the single major employers overall and it is a big question what development and employment opportunities, if any, have opened up in these towns in the meantime.

Another development causing even more concern is the substantial slowdown in Serbian-owned SMEs exports which (according to administrative data) in 2024 declined by 3% relative to 2022.

2. Factors of financial risk: Bank capitalization and public debt trajectory

Authoritative observers like the IMF and World Bank give relatively high passing grades to the stability of Serbia’s macroeconomic framework. Serbia’s debt received an investment rating and this was further raised subsequently.

II.B – The REER: The tip of the competitiveness iceberg

Over the past years Serbia has seemed to defy the maxim that in order to grow sustainably, an economy needs to have a conducive business environment and strong institutions. Certainly, the macroeconomic stability has served it well. However, in this section we argue that the real appreciation of the dinar has been extremely strong recently. This, together with the strong rise in real wages is now putting Serbia’s competitiveness at a very substantial risk. Fixing these issues requires institutional strengthening as well as a change in policies.

The relatively high levels of external and even government investment did not elicit a commensurate supply response from the economy. Growth did accelerate for a while, but domestic investment remained low and the increase in domestic production was relatively subdued.

B.1 Is the real exchange rate becoming a serious risk?

The Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) has appreciated significantly, raising concerns about competitiveness. While manufacturing exports (particularly from Stellantis and tire production) have shown resilience, the ICT sector is slowing and domestic SME exports are declining substantially.

B.2 Structural factors of the REER appreciation

To understand how institutional quality and policies affect the real exchange rate it is important to understand how the real exchange rate is affected by, in fact it is a reflection of, the relationship between the prices of traded and non-traded goods.

Four aspects of Serbia’s economic policy exacerbate the REER:

- Fiscal discrimination: Domestic investment is treated less favorably relative to foreign investment

- Promotion of non-tradables: Fiscal and central bank policies promote investment in non-tradables

- Credit discrimination: Monetary policy discriminates credit to the economy versus households, and within credit to the economy – of SMEs relative to large companies

- Suppressed supply response: Policies suppress the domestic supply response

The REER depends on the (excess demand) pressure exercised on domestic prices (non-tradables) relative to tradables. The balancing of these pressures is accomplished as much by fiscal as by monetary policy. And both these policies are framed by the external macro environment and the structure of the economy.